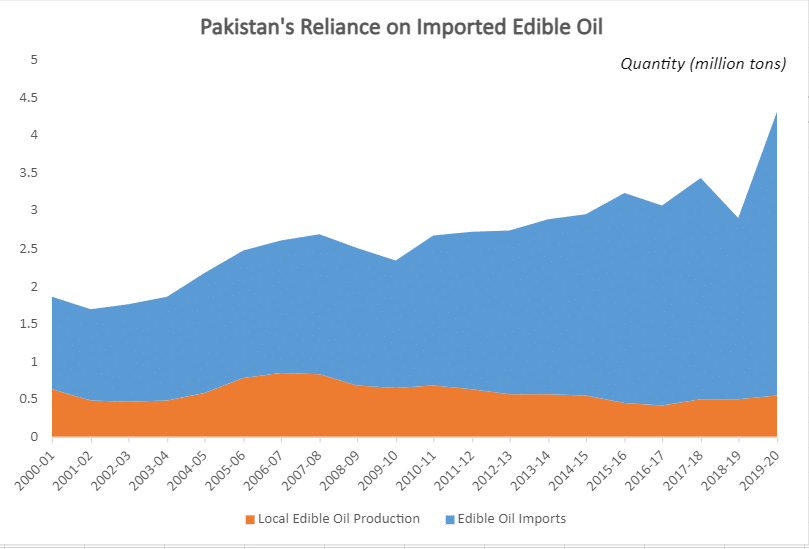

Edible oil imports are the mystery behind Pakistan’s massive $9 billion food import bill, contributing to nearly half of it and in a time of extreme need for self-sufficiency, everyone wonders what’s the way out.

Pakistan’s per capita consumption of edible oil has risen from 6 kg per annum to 18 per annum between 2000-2020. This is caused mainly by population boom, increase in income levels, rising demand for fast food and trend of eating out.

More than 80 percent of the national demand is met through imports, with more than half of the local production coming from Cottonseed, followed by 32 percent from Rapeseed & Mustard, 7 percent each from Canola and Sunflower.

Palm Oil and Palm Olein account for the majority of imported Edible oil in the country. Pakistan imported 3 million tons of Palm oil worth of $3.64 billion during FY23 while Soybean Oil imports stood at 220,000 tons or $315 million during the same time.

There are other sources as well for edible oil but for this, we will be solely focusing on the ones already having a major share in consumption and the policy decisions around them rather than potential alternatives like Olives, Coconut or locally growing Palm.

We will also be excluding Soybean which has a world of its own, was not included in the major policy choices of recent years and despite being important for a healthy edible oil blend, it is mostly imported for meal requirements at the moment.

Why does Pakistan Lag in Edible Oil Production?

In 1977, the Pakistan Edible Oil Corporation (POEC) launched the first organized effort to promote oilseed crops but was dissolved in 1979.

Subsequent initiatives, including a seed division in the Ghee Corporation of Pakistan (GCP) and the National Oilseed Development Project, faced challenges and were eventually abolished.

The Pakistan Oilseed Development Board (PODB), established in 1995, focused on Canola cultivation and introduced oil-bearing trees but saw reduced influence after the 18th amendment in 2011.

Pakistan initially lacked oilseed crop varieties with high yield potential and suitable for the local climate but after decades of research, we have solved that part of the equation to some extent. But you see that edible oil is not a crop, but a whole industry and that’s where challenges only begin to emerge.

The first thing one notices from the above history is the absence of consistent policymaking, which scares off any investors and is the worst enemy of building anything. From official policies down to university curriculum, until a few years ago, oilseeds were always considered and treated as minor crops.

The only consistent policy that one sees is allowing the liberal imports of Palm oil that maintain domestic availability of oil but does nothing to handle the issue in the long run.

Secondly, having variety is not enough. You also need a seed multiplication system that can ensure the availability of quality seeds at scale and affordable prices. Imported hybrids have low adaptability and are highly expensive.

More so, if we start depending on other countries for hybrid seeds rather than edible oil, we will just be replacing one problem with another one. But there is a bigger issue.

Pakistan’s local Edible Oil production dropped by 21 percent from 477,00 tons to 374,000 tons between 2018 to 2021 but has recovered to 496,000 tons since then.

“Lack of market price assurance is the biggest hurdle for the farmers to adopt these crops because the farmer would grow any crop for profit but Canola (which is most suitable) competes with Wheat which is a political crop and so more profitable” stated Saad Bin Mustafa, Oilseed Researcher at Ayub Agriculture Research Institute (AARI) while talking to ProPakistani

He recalled that last year farmers received Rs. 8,000-9,000 per maund for their Canola harvest (probably due to import curbs, dollar price hikes) but this year prices have again dropped to Rs. 6,000 and so farmers are moving towards Wheat.

He added that they are advocating for replacing low-productive areas under Wheat cultivation, especially in Barani regions, to oilseed crops through policy measures and industry development, but sustainable policies are needed in this regard.

The lack of modern machinery to reduce massive post-harvest losses, absent credit facilities and low demand for local produce due to open imports are also considered hurdles.

No Answer to the Wheat Question?

Both Sunflower and Canola compete with Wheat, which is a staple, but even if farmers rise above their subsistence practices of only growing for their own home and try moving to other crops, the government provides a good enough support price to make sure the otherwise.

The policy has made Wheat a strong choice from a business perspective as well, as the safest bet in a volatile industry. Wheat support price is the nearest thing farmers have to a social security framework, and most may not survive without it.

It also enables farmers to spend more on Kharif crops, so it also has a cyclical effect in not only raising the living standard of farmers but also the whole profile of the sector.

But what about the oilseed crops that we want to grow?

A 2020 study by AARI noted that Pakistan need nearly 7.46 million ha under oilseed cultivation to achieve self-sufficiency in edible oil production, and the study envisions replacing the ‘surplus’ area under Wheat and Sugarcane with oilseeds.

But if we have surplus Wheat, why we are importing nearly 3 million tons of it this year to meet the demand? Well, many analysts have raised eyebrows on the government’s claims of bumper Wheat production, so it’s quite possible we don’t have a surplus. Losses and smuggling take care of the rest.

Mustafa stated that the goal is to take the Wheat average to 40 maunds per acre through best agronomic practices and shift low-productive regions in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan to Oilseeds through policy interventions.

Palm Oil Imports – Too Liberal?

The 2020 study also found that locally produced Canola and Sunflower seed and oil are available to the oil industry at more economical prices without involving many channels in the import of these commodities.

Some experts also blame the inverse policies of the All Pakistan Solvent Extractor Association – APSEA and Vanasptee Ghee Mills Association, claiming they undermine growers’ interests.

“The non-judicious import in bulk is also a major concern which keeps the prices of local produce low and future policies should consider it making complementary to buy certain percentage from local sources and at appropriate prices,” added Mustafa.

But unlike corn and sugar, oilseed cultivation is too fragmented across the country and building a strong network of processing and distribution channels also needs to be incentivized to enable growth.

There are 100 units of APSEA operating across the country for oil extraction and meal production, having a capacity of 7 million tons against annual consumption of only three million tons so there is not much incentive or even need for an expansion as much as relocating the facilities near production regions but as mentioned earlier, there is no big enough cluster of local cultivation to relocate to at the moment.

It’s also proposed that the edible oil industry should promote a contract farming model, the same one deployed by Pepsi for Potatoes, by Rafhan for Corn and most importantly, by the one and holy, the sugar industry.

“The case is the opposite. The local sources are always consumed first and the rest of the demand is imported. Even if the government doubles the tariff, imports will remain the same because it has the market, only prices will go up,” clarified Shakil Ashfaq, Ex-Chairman and Member of Executive Committee APSEA while talking to ProPakistani.

He also revealed that the current tax exemption on local edible oil is also incentivizing off-book settlements and the government needs to look into it. Talking about the contract farming preposition, he said that APSEA is quite open to it and in fact, some of their members are already working on it.

In 2017-18, Punjab launched the Oilseed Promotion Initiative, offering a Rs. 5,000 per acre subsidy and securing a procurement price of Rs. 2,500 per maund for Canola and Sunflower.

Despite the success, Sunflower cultivation fell short of the target at 92 percent, and the announced procurement prices were not enforced, causing disappointment among farmers. The initiative provided Rs. 0.675 billion in subsidies, resulting in a total value of Rs. 3.945 billion and a net benefit of Rs. 3.27 billion for the province.

In 2018-19, the program was extended to include Sesame, but Canola subsidies were not realized, and Sunflower subsidies faced delays amid a change in government, compounded by discouraging prices and seed supply challenges from the previous year.

National Oilseed Enhancement Programme (2019-24):

The latest and ongoing initiative to promote Oilseed cultivation was a five-year programme, launched in 2019 in the Prime Minister Agriculture Emergency Programme under the Ministry of Food Security & Research (MNFS&R) through four provincial governments and the Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC).

The program proposes several key interventions, including the registration of oilseed growers for subsidy eligibility, offering a subsidy of Rs. 5,000 per acre (up to 20 acres), providing a 50 percent subsidy on oilseed machinery purchases and ensuring hybrid seed availability through national and multinational seed companies and research institutes.

It also aimed to implement national hybrid seed multiplication for sustainable oilseed production, establishing a procurement center with the All Pakistan Solvent Extractors Association, disseminating production technology through various media channels and SMS, organizing farmer gatherings, arranging demonstration plots in oilseed growing areas, and recognizing the best growers at district and provincial levels through yield competitions.

NEOP Performance Overview during 2019-23:

According to government documents viewed by ProPakistani, the total project cost was estimated at Rs. 10.96 billion, but only Rs. 3.19 billion or 29 percent of the funds have been released during the first four years of the programme.

It was supposed to provide subsidy (Rs. 5000 per acre) over 0.94 million acres during the first four years, and 0.76 million acres or 81 percent of it has been achieved so far to nearly 200,000 growers, despite the huge shortfall of funds.

The 50 percent subsidy target for farm machinery was set at 764 implements, only 36 percent of it has been realized and some 339 or 68 percent demo plants have been established so far against the target of 471. Though the target of farmer gatherings has been achieved already.

The target for subsidy provision (in acres) for Sunflowers has been achieved up to 98 percent, but the progress for Canola and Sesame is still lagging at 69 percent and 78 percent.

During the four years of the project, oilseed production for Canola and Sesame increased by 300 percent and 281 percent, respectively against the four years before the project. The cultivated areas also reported a 216 percent and 175 percent rise respectively for both crops during the same time.

Sunflower production however reported a mere 0.6 percent increase in four years of the project with a massive 20 percent decline in cultivated area.

This programme too may have been a success on its own but if we look back at the graphs discussed, both the total cultivated area for oilseed and oilseed production declined between 2018 to 2023. That is because of a big decline in Cottonseed production and rest of the crops are struggling to make it up for.

At the same time. While canola production and cultivation reported a 60 percent and 103 percent increase from 2019 levels, Sunflower production and area have declined by 6 percent and 30 percent between the same time.

One big exception is Sesame which was a major part of the programme and had been included as an export crop rather than an edible oil source and it’s proven quite a success. Pakistan recently became 5th largest exporter of Sesame in the world, bringing in $351 million during the first five months of FY24 and noting a 294 percent growth YoY.

The Way Forward

The biggest challenge is of course the funding but unfortunately, it’s still not the top priority, as evident from the 70 percent funding shortfall under NOEP during the first four years of the project.

From 2019 to 2023, Pakistan spent nearly Rs. 3,408 billion on edible oil and oilseed imports, but the public sector investments during the same time stood at Rs. 3.19 billion or 0.09 percent of the foreign exchange drained out of the country. Priorities are everything.

With priorities, should come a consistent policy that can bring long-term investments in the sector. Former Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif also constituted an Oilseed taskforce in his tenure but not much came out of it.

More work needs to be done on seed multiplication, marketing and procurement, and intra-industry cooperation so that it can require least government intervention.

There also needs to be more focus on demand-side action, rather than pumping subsidies only. It includes promoting more contract farming and developing cluster regions to incentivize the relocation of extraction facilities. Farmer cares about the profit and not the subsidies and sadly, when it comes to oilseed, both are not the same.

Source : Pro Pakistani